The race against customers

Suppose that a critical bug is hiding in a release of your software. There’s some average time for tests to find this bug. But you are not the only one testing your code — every day, your customers are using your code; after a certain number of customer “test hours”, they are likely (on average) to find it. And they are probably doing a lot more cumulative testing than you did! Someone will find it first, you or them.

The race against yourself

Consider a situation where an engineer writes some buggy code, runs a test, and immediately encounters a new failure. The path to resolving that issue is very direct — the engineer simply reverts the change that they just made, and thinks a little bit harder about how to do it correctly. Time cost of the bug: almost zero. Now consider a situation where an engineer writes some buggy code, runs a test, the test passes, and the code is accepted into a new release. Months later, the bug manifests in some different test or in production. The cost of resolving this bug could be huge, potentially so huge that it’s not even worth trying to fix! Rather than just reverting some recently modified code, your team now needs to do an extensive root-cause analysis to troubleshoot the issue. Once the underlying problem is found, it will still be expensive to fix. The team may have forgotten the details of why the change was made, and what the mental model was that led to it. Even worse, the engineers involved may have switched teams, gotten promotions, changed jobs, or retired. Either way, a vast amount of contextual knowledge associated with the bug has been lost, and will need to be painfully relearned in order to resolve the issue. Even if your customers aren’t the ones finding it, it’s much cheaper to solve a bug when you find it quickly. This is the race against yourself.

Optimal usage

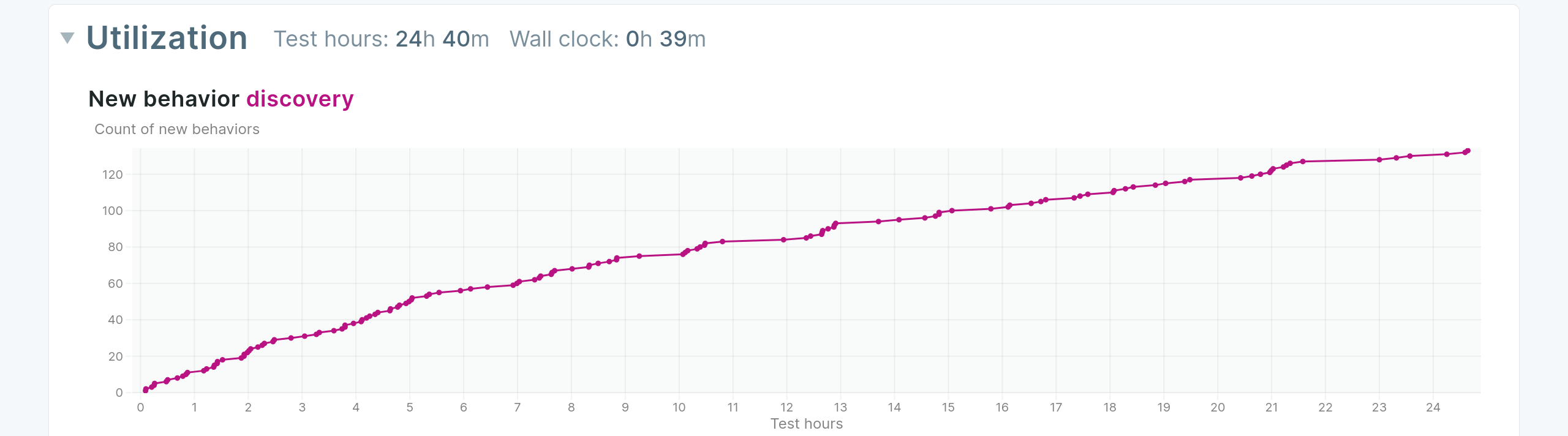

Let’s return to our original question: “how should I size Antithesis?” The short answer is, with enough parallelism to ensure that you are regularly winning both the race against your customers and the race against yourself. Every organization is different — different numbers of customers, different release cycles, different quality goals, different engineering practices, not to mention different software! So there’s really no one-size fits all answer to this question, instead we recommend taking an empirical approach. If you do a proof-of-concept with us, by the end of it we should have enough data about real-world bugs to make a recommendation. If you instead decide to jump straight in with Antithesis, feel free to start small with a single 48-core instance and then continuously re-evaluate as you get more data about whether you’re winning these two races. If a bug is found in production, or by your customers, you should demand an explanation from us. It could be that your Antithesis setup is misconfigured, such that the circumstances leading up to the bug can never occur. Or it could be that there’s a limitation in your test template that means the bug will never or almost never be seen. But there’s also a chance that the answer is simply that you aren’t running your tests with enough parallelism, so we would have found it eventually, we just didn’t find it in time. When this happens, it’s a pretty good indication that you should be testing more. If a bug is found in your Antithesis tests one night, is it found every time thereafter? If not, you should demand an explanation from us. A bug that is found occasionally or unreliably is like a flashing red warning indicator that your tests are not powerful enough. Again, the reason could be misconfiguration, a weak workload, or not enough parallelism. It’s very important to find out which one is happening, because they suggest different solutions. Antithesis provides a tool to help diagnose misconfiguration and workload problems. The triage reports you receive contain a graph in the “Utilization” section which plots new behaviors discovered over the duration of a single test. It’s in the nature of autonomous testing for there to be diminishing returns with each new test, so it’s normal for this graph to look roughly logarithmic. However if the graph hits a hard horizontal asymptote, that’s a sign that something is wrong. It means that additional test cases aren’t provoking any new behavior or code paths in your software, which is often a sign that something is misconfigured, or that your workload isn’t varied enough. In any case, more testing will not help find more bugs in this situation.