You can read more about the specifics of the system in our Antithesis environment documentation, but for our purposes, you can think of it as a Linux system that’s been customized for testing.

environment object to access the following features that relate to the Antithesis environment:

- getting system logs with environment event sets

- listing containers

- extracting files to view locally

- injecting files in a container after it starts

- configuring fault injection

- profiling CPU usage

The environment object

Inside a multiverse debugging session, theenvironment object represents the system as a whole. In each moment, the Antithesis environment is in some state. There are probably containers running your software, there may be Antithesis faults in progress, and there are certainly some background services supporting the system.

When you begin your session, the environment object is already defined for you:

Getting system logs

Sometimes, when you’re diagnosing a problem, it’s helpful to see what’s going on with the system as a whole. System logs are available through theenvironment object as curated event sets.

When events are the result of readable (non-binary) program output, an event is sent each time the output contains a newline character.

environment.containers.events: output from all of the containersenvironment.containers.meta_events: changes to containers (create, start, stop, etc) as seen by the container management systemenvironment.sdk.all_events: all of the events that have been processed through the Antithesis SDKenvironment.sdk.assertions: assertions defined with the Antithesis SDK which have been encounteredenvironment.events: the main event source, including the sources aboveenvironment.fault_injector.events: high level information about the status of the fault injectorenvironment.fault_injector.faults: information about each of the discrete faults introduced by the fault injector (this does not include background chaos like thread interleavings or baseline packet drop rates)environment.background_monitor.events: raw output from the Antithesis system utilization monitor (Warning: this is a new feature and its format may be unusually unstable!)environment.journal.events: the main logger on the system, including for various daemons. It can be verbose, but it is the right place to notice (for instance) the system OOM-killer. (read more at man journald)

Listing containers

You can list all of your containers as of some moment.notebook output

Extracting files

Sometimes, the best tool for inspecting a file is one you have locally. In cases like that, you can extract the file and download it.notebook output

Injecting files

Sometimes, you may want to inject a file in your container after it’s started. In cases like that, useinject_file().

Configuring fault injection

If you’re exploring a moment from the middle of a test, Antithesis might have been disrupting the network or other containers. If you want to stop these faults, either to see whether your software recovers or to make other debugging clearer, you can useenvironment.fault_injector.pause, and if you want to resume, you can use environment.fault_injector.unpause.

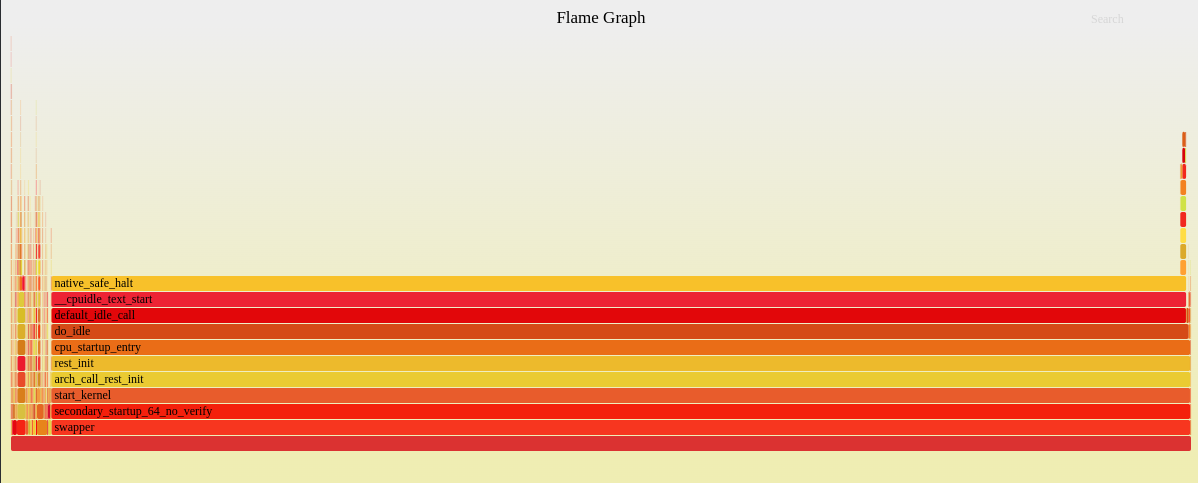

Profiling CPU usage

The Environment includes a CPU profiler, which is a powerful way to investigate what’s happening during some part of a branch. Here’s what it looks like to use the profiler.

Running commands

To run a command in one of your containers, you can use a bash fragment. Commands return a process object.Since we know that many lightweight containers don’t include bash, Antithesis mounts a shell and assorted shell tools into every container at runtime, making it possible to run bash commands even in minimal containers.

Running a command with .run()

Most of the time, when you want to run a command, you want to run it to completion. If you call .run() on a fragment, it will run until it finishes, advancing the branch until the command has exited.

If the command doesn’t exit, .run() will fail after 30 virtual minutes have passed. You can supply an optional timeout to change how long it waits.

notebook output

Starting a command with .run_in_background()

Sometimes, you want to start a long-running command and not wait for it to complete. When that happens, you can use .run_in_background(). Unlike .run(), .run_in_background() only advances time on the branch until after the command has been delivered. It might not even be started until time has advanced on the branch!

If you print the result, you’ll still see the output as it comes in (see the process object notes for more of an explanation).

notebook output

Bash fragments

The multiverse debugging environment supports running shell commands with bash fragments. A bash fragment is a JavaScript tagged template literal containing the command that you want to run.Process objects

When you run a command in our environment, the result is a process object representing the execution of that process on the branch. You can print a process to view its output.notebook output

help(proc) for more details on what you can do with a process object.

Highlights

- Process-specific event sets, including

proc.events,proc.stdout,proc.stderr, andproc.exits. proc.pidis the PID of the process inside our virtual system.proc.exited_by(moment)will returntrueif the process existed in the branch that ends with the supplied moment, and had exited.proc.exit_codeis the exit code that the process returned.

Background processes

Whether you use.run() or .run_in_background(), the process will have the same shape, but the behavior may be slightly different.

In particular, when you get a Process object from .run_in_background(), its properties will be true as of the current state of the branch it was run on.

proc.exit_codewill beundefinedif the process hasn’t returned yet.proc.pidwill beundefinedif the process hasn’t forked yet.

print() a process that results from .run_in_background(), you will see the events associated with the process on the branch that it was constructed from, as though the print were written below the last update to the branch in the notebook.